USTA Eastern Mourns the Loss of Past President Dan Dwyer

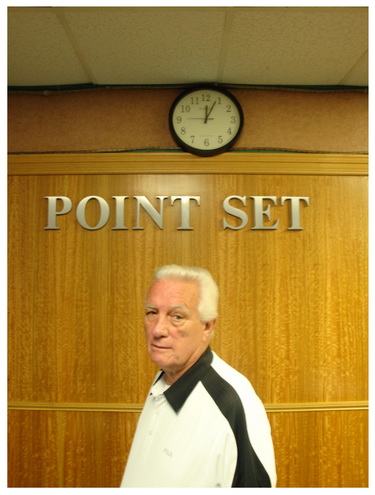

Daniel B. Dwyer, a managing partner at the Point Set Indoor Racquet Club in Oceanside, N.Y., and a past president of the USTA Eastern section, died suddenly of a heart attack on May 25. He is survived by his daughter Kimberly, son Shawn and three grandchildren. Danny Dwyer was the Johnny Carson of tennis. He disarmed audiences with the same sly charm as Carson, the same edgy sense of humor and the tenacity to put himself on the line for decades. Danny didn’t have an Ed McMahon to keep his show rolling, but his staff at the Point Set Indoor Racquet Club helped him tone down the “I want it done now!” mentality he brought to the business of recruiting people to the game.

“When you play Danny, all you have to do is kick your serve to his backhand and you’ll win,” joked Perry Aitchison, who worked with Danny at Point Set for years. Danny’s first retort to that news was unprintable. Then he deadpanned: “Ten years ago, I would have run around my backhand; today I’ll only play Perry if he’s blindfolded.”

Danny had the classic Irish temper dipped in honey. He was an optimist and always believed the best was yet to come–especially to those who are a little less powerful. If he thought a cause was worth his time, like wheelchair tennis and tennis for children with multiple sclerosis, he got involved and never looked back.

Danny’s brother Jim remembered a 1962 national incident that Danny became involved in when he was playing tennis on scholarship at St. Edward’s University in Austin, Texas. Acting officially in his role as the president of the student government, he sent a congratulatory telegram to James Meredith, the first African-American to be accepted into the University of Mississippi. His gesture showed up in local newspapers, he received death threats from the Ku Klux Klan and 20 classmates stood guard outside his dormitory room.

Brother Raymond Fleck, C.S.C., the university’s president, summoned him to his office. Danny said, “You can’t tell me that sending the telegram to Meredith was wrong. It’s what you taught us.” Brother Fleck replied, ‘It’s not wrong. But maybe you could do it more quietly in the future. We just lost a $10,000 donation.’

“I’m a rebel if there’s a cause.” Danny always said. “I’ve spent most of my life trying to eliminate prejudice of any kind; it’s the biggest waste of human energy.”

In the late 1970s, Danny got a phone call from a wheelchair athlete who wanted to enter a tennis tournament. He quickly made Point Set wheelchair-accessible and began hosting one of the country’s first, free wheelchair tennis clinics. By the mid-1980s, he had founded the National Tennis Association for the Disabled and the international Lichtenberg Buick-Mazda wheelchair tournament. He became the USTA’s first wheelchair committee chairman, and became one of five people appointed–and the only American–to serve on the International Tennis Federation wheelchair committee.

Danny’s children, Shawn and Kimberly, grew up feeling comfortable around physically and mentally challenged people. George McFadden once beat Bobby Curran in a wheelchair match, took a shower and walked out of the locker room wearing his prosthesis. Kimberly, then 7, ran to her father in tears: “Daddy, we have to disqualify that man; he beat Bobby, and he can walk.”

In Danny’s world, tennis-careers-in-the-making seem to depend on who’s picking up the tennis balls. In 1952 at age 12, he retrieved tennis balls for Alex Mayer at the Burwood courts in Flushing for 25 cents an hour just to hear what the great coach had to say. Every once in a while, Mayer would give him 20 minutes of his time. “I started as a maintenance person and became a club manager,” Danny said. “You never know what’s going to happen.”

A young Mary Carillo picked up tennis balls for Danny at the Douglaston Club and you know what happened to her: She went on to win a Grand Slam title and become one of the sport’s most visible television analysts.

A young Mary Carillo picked up tennis balls for Danny at the Douglaston Club and you know what happened to her: She went on to win a Grand Slam title and become one of the sport’s most visible television analysts.

“I would stand outside the fence and listen to him teach,” Mary has said. “He didn’t realize he was teaching two people. We all grew up with Danny. He totally shaped my life. You always wanted to catch his eye. He had such a presence and still does. When I was inducted into Eastern’s Hall of Fame (in 1994) my brother Charles said, ‘Good God, Danny looks like a Monsignor now.’

“I asked Danny that night how much he charged back then. He said eight bucks an hour. I said to him, ‘Well, I owe you about $400,000. Will you take a check?’”

Danny always told his junior students that their goal should be number one in the world. When parents told him that their kids just wanted a respectable ranking for a college scholarship, he said frankly: “You wouldn’t complain if I was pushing your child to get into Harvard. Go for the gold even if you only wind up with a bronze. Otherwise, why play tennis?”

He had used that tactic with ten-year-old John McEnroe when McEnroe won a tournament at the Douglaston Club. “You will play at Forest Hills some day,” Danny told him, and it worked! He challenged other famous Eastern juniors he worked with—among them Sandy and Gene Mayer—and they took him seriously, too.

“Danny was there at the beginning,” John McEnroe has said. “He helped me when we first joined the club and started to learn the game. I want to personally thank him on behalf of myself and my family for being there.”

Danny rose through the ranks as a player and coach to become one of the game’s most visible national and international administrators. He was the manager and part owner of Point Set in Oceanside, N.Y. He was also the head tennis pro at the Woodmere Country Club for over 50 years. For four years, he was a tournament director at the New York City Mayor’s Cup, the world’s largest interscholastic event, with over 800 participants. He chaired the Catholic High School Tennis League when he taught biology and English at his alma mater, Holy Cross, in Flushing. He served in every volunteer position on the USTA Eastern board—from Long Island regional vice president to president of the section and the Junior Tennis Foundation. He was among the first sectional leaders to support league and schools programs for recreational players. He has also been inducted into the St. Edward’s and Holy Cross Halls of Fame.

“He’s compassionate,” Danny’s brother Jim said. “He could have made more money when he graduated from college, but he went back to teach at Holy Cross to repay them for helping him get a scholarship. He’s the champion of those who need a break. He’ll push them forward. It doesn’t always work but he never gives up. He follows through.”

“Danny is a blessing,” his family has said. “He’s Santa Claus.”